José Alvear Restrepo Lawyers’ Collective, February 1, 2007, Bogotá, Colombia

“It was on August 29, 2003, when the body of Ever de Jesús was found at the Valledupar city morgue with his face disfigured, dressed in camouflage, and presented by the army as killed in combat against the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). But we all know that it isn’t true, that it is way the military silences the community leaders who dare to speak out.” [1] Paradoxically, from August 29 to August 31 of that year, the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office was carrying out a workshop in the community of Chemesquemena, which included the presence of an official from the Ministry of the Interior’s Ethnicities Office, the Human Rights Delegate for Indigenous and Ethnic Minority Affairs, Gabriel Mujuy, and the Community Human Rights Liaison.

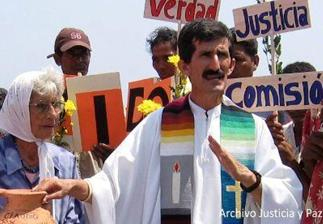

Coronel Hernán Mejía

Ever de Jesús was returning from Valledupar to apply for economic support for the murder of his father, Hugo Montero, who had been killed by paramilitaries on April 16 of the same year. “Three armed civilians took him off the public transportation he was traveling on with several other persons, including Gabriel Mujuy, the Human Rights Delegate for Ethnic Affairs of the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office. Ever de Jesús was heading to Guatapurí, after getting some documents in order to access the Assistance Program for Victims of the Armed Conflict, a program that is a part of the governmental Social Solidarity Network.”

Ever de Jesús, though, was not the only persons murdered that year. According to Jaime Arias, cabildo governor of the Kankuamo people, 44 cases were denounced that year up to the month of September, [2] the majority attributed to the paramilitaries. At the time Colonel Hernán Mejía was the commander of the La Popa Battalion based in Valledupar (Department of Cesar), when it became one of the battalions with the most kills in combat registered from between 2002 to 2004, according to the witness that denounced Mejía’s actions and links with paramilitarism (a former junior army officer and subordinate of Mejía). [3]

The murder of the 19-year-old Ever de Jesús, who at the time was a promising young leader for the community of Guatapurí, is probably one of the cases for which Juan Manuel Santos, Minister of Defense, announced last Friday he had removed Colonel Hernán Mejía from his post for his “links with paramilitarism, human rights violations, and cases of kills that may not be the result of military operations, rather acts of corruption“; and who since August, 2006, has commanded the troops in Santana (Department of Putumayo). According to information gathered by the Kankuamo indigenous people, [4] during the month of August 2003, seven persons from their community were murdered by paramilitaries. Of special concern is Jhon Jairo Montero Maestre, who was bound and taken from his house located in the Kankuamo community of La Mina, after a group of approximately 60 heavily armed men had just arrived. Jhon was taken to a nearby place known as El Charquito, where he was shot dead in front of several witnesses from the community.

During this same paramilitary incursion of August 25, 2003, and in the same manner, the 18-year-old Santander José Arias Arias was killed, along with countless other violations committed against this population.

A few days previously, on August 11, 2003, Andrés Ariza Mindiola had been murdered by paramilitaries in Atanquez during a paramilitary incursion of his farm, which also robbed him of 56 cattle. Alciades Arias Maestre was also murdered in the township of Los Haticos.

According to Alirio Uribe from the José Alvear Restrepo Lawyers’ Collective, “in the complaints and denunciations presented before the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office and the humanitarian missions meant to follow up on the human rights situation of the indigenous peoples of the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta and the Perija Mountain Range, the armed forces present in this area of the country are held responsible, particularly in the department of Cesar, for allowing paramilitary groups to freely move about in these areas, establish their bases of operation within indigenous territory, jointly patrol and carry out actions in order to terrorize, as well as indiscriminately attack the population.”

Likewise, Alirio Uribe states that in some cases the national army is attributed to being responsible for grave breaches to international humanitarian law, including extrajudicial executions and cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment inflicted against indigenous persons and their authorities.

At the time, reports gathered by the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office stated that a paramilitary base was located in the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta (in the area under the jurisdiction of the municipality of Valledupar) at a place called La Mesa. This paramilitary base was just 6 kilometers, or 10 minutes, from the military base for the La Popa Battalion. It was also under the command of the paramilitary David Hernández Rojas, alias “39”, who as reported by the magazine Semana in its latest edition was a close classmate of Colonel Hernán Mejia.

Nevertheless, while the national government was fully negotiating with these paramilitary groups, in 2005 several persons were murdered in the areas surrounding the paramilitary bases, which continue to exist in La Mesa and Río Seco. As should be remembered, the last groups belonging to the Northern Bloc of AUC demobilized at La Mesa on March 10, 2006. At this time the High Commissioner for Peace, Luis Carlos Restrepo, announced the demobilization of 1,220 members of combat fronts and 1,325 members of the fronts offering social support, though only 793 weapons were surrendered.

Due to the grave situation of extermination faced by this indigenous people (which has also caused mass displacement from their territory), it must be pointed out that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights granted them precautionary measures of protection on September 24, 2003. Additionally, because the Colombian State did not fulfill with its obligations and the irreparable damages to this people continued, on July 5, 2005, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights decreed provisional measures of protections, which had been jointly petitioned by the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia and the José Alvear Restrepo Lawyers’ Collective.

However, the so-called paramilitary demobilization process has not been able to bring about the dismantlement of the paramilitary structures, which continue to intimidate and control territory under the currently re-baptized “Black Eagles”, identified by the population as being the same persons belonging to the former Tayrona and Mártires del Cesar Blocs of the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC).

Lastly, it is odd that the government has only proceeded to remove Colonel Hernán Mejía from his post, when he should have been definitively separated from his duties, through exercising the Presidential discretional power in accordance with the relevant constitutional mandate.

The National Indigenous Organization of Colombia and the José Alvear Restrepo Lawyers’ Collective hope an investigation is carried out by the Attorney General’s Office that contributes to definitively clarifying the facts concerning the crimes committed against the indigenous peoples of the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta.

…………..

1. Testimony.

2. “Jaime Arias, cabildo governor of the Kankuamo people, spoke out against the extermination of his community. According to Mr. Arias, 200 members of the Kankuamo community have been murdered since 1986, and 44 cases have occurred this year.” El Tiempo Newspaper, September 26 2003.

3. Semana Magazine. De Héroe a Villano. January 29, 2007.

4. Kankuamo Indigenous People. Hoja de Cruz. 2006.